According to a popular quotation that has been apocryphally attributed to a wide cast of characters including Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin, and even Steve Bannon, “there are decades in which nothing happens, and weeks in which decades happen”. While the origin of the statement is uncertain (it may, in fact, have biblical roots), as we all now mercifully exit one of the more difficult and volatile years in recent memory, the line certainly seems to ring true. And for advisors like us who make our living selecting and managing investments, 2020 absolutely seemed to include a decade’s worth of market activity, all compressed into less than 9 months—from bull market to bear, right back into a(nother) bull market, all in record time.

The whipsaw nature of the market’s moves—especially when combined with the disruption to our daily lives—left many investors paralyzed and potentially scarred by the experience. What we knew to be true as advisors, though—and tried our best to impress upon our clients—is that the impact of a bear market on one’s broader financial situation can depend entirely on one’s stage of life. For some, bear markets are to be avoided at all costs, whereas for others, they are nothing to be feared at all—and in fact, should theoretically be welcomed with open arms. We’ll explain why.

Timing matters

The difference, from a financial planning standpoint, boils down to what is known as “sequence of returns risk”. At its core, this dynamic recognizes that considering only the “average” returns over an extended multi-year period is of limited use in predicting long-term financial success or failure. Instead, there is an important interplay between the timing of market returns and the timing of cash flows into (or out of) a given investment portfolio.

Basic financial planning often assumes consistent, linear investment returns (say, 5% annual growth into perpetuity), but reality is typically much messier: according to a recent analysis by Goldman Sachs, dating back to 1928, only 28% of calendar years have produced single-digit percentage gains or losses. Stable markets are elusive, and volatility is the norm, not an exception. To help illustrate the impact of different market environments, we considered three separate (simplified) market paths, and then studied the performance of three different hypothetical investors in those varied market scenarios.

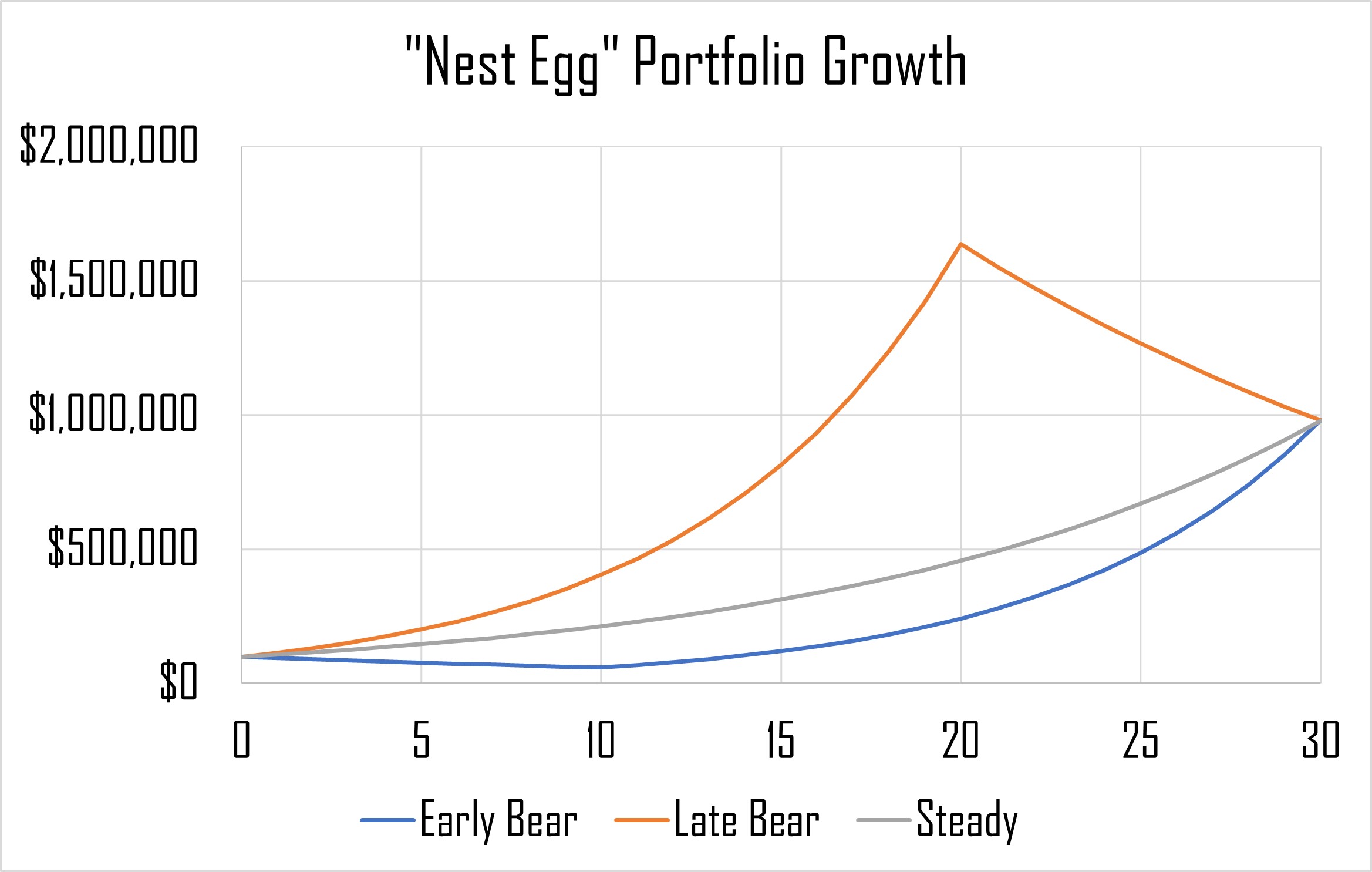

For the market environments, we wanted to set the starting and ending points for “the market” essentially constant—that is, in all cases, we wanted the market to start and finish at the same points, varying only the path that was taken (the timing of gains and losses). In the first scenario, which we’ll call “Early Bear”, the market struggles for a full decade, losing 5% each year for 10 years. It then rebounds strongly, posting 15% annual gains each year for the next 20. In the second scenario, “Late Bear”, the exact opposite occurs—15% gains for the first 20 years, followed by 5% annual losses for the next 10. Finally, we considered a linear market environment (“Steady”), with consistent 7.9% returns each year for 30 years. As you’ll see in our first chart, for an investor with a static starting balance and no flows into or out of the account, the outcomes will be essentially the same, regardless of the path taken.

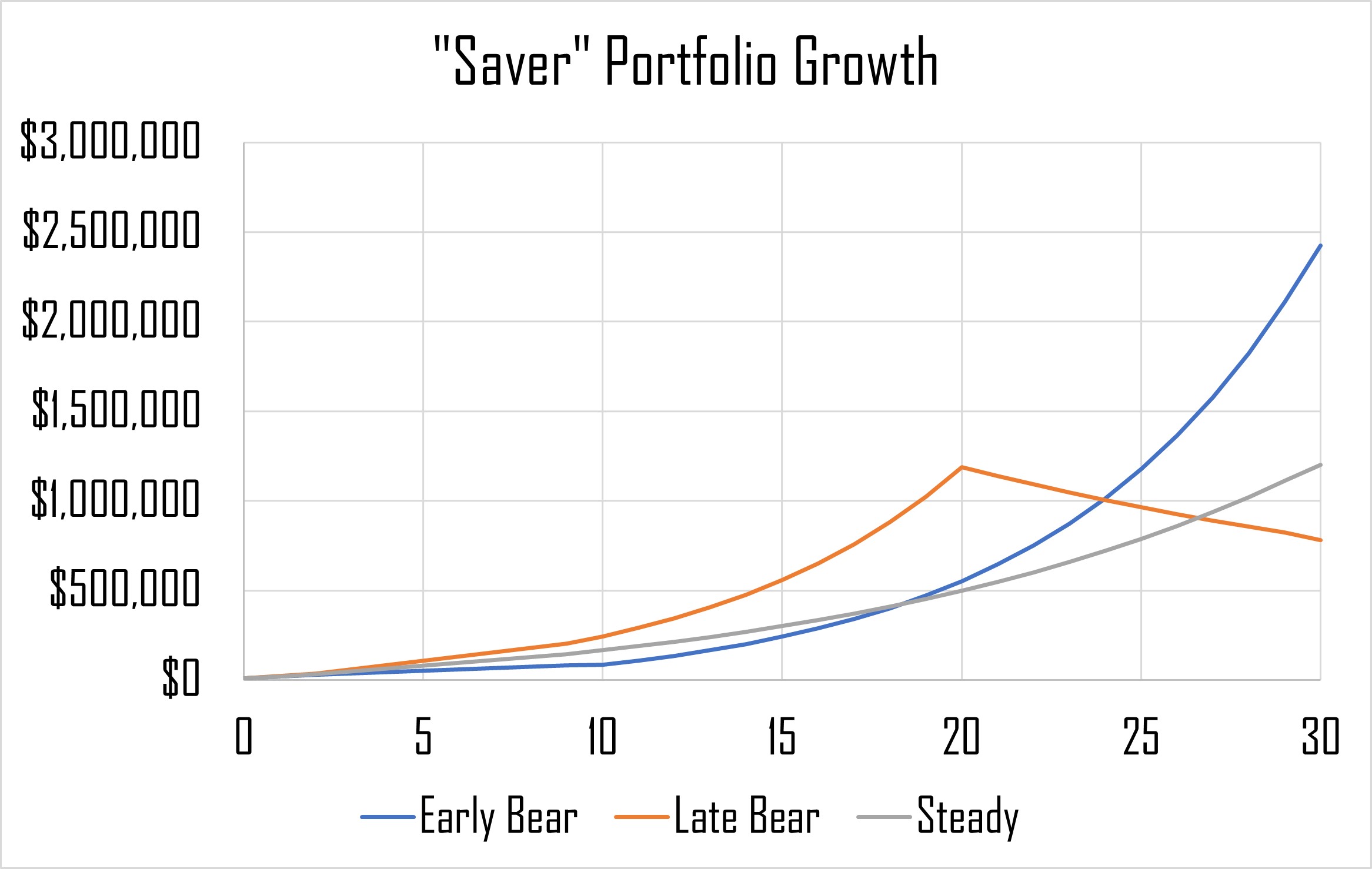

This “Nest Egg” investor doesn’t need to worry about sequence; the average annual return is all that matters. But once we introduce inflows (or outflows), the math changes dramatically. Next, we’ll consider a younger “Saver”, who starts with a $0 balance but contributes a consistent $10,000 per year to the portfolio.

For the “Saver”, the “Early Bear” market is by far the optimal scenario, leading to a final account balance that is more than 2.5 times higher than the “Steady” investment return. Low early returns allowed the account balance to gradually accumulate, with the Saver buying in to the market at cheaper prices. By the time the market rally arrives, the account balance is large enough that the investment gains are supersized.

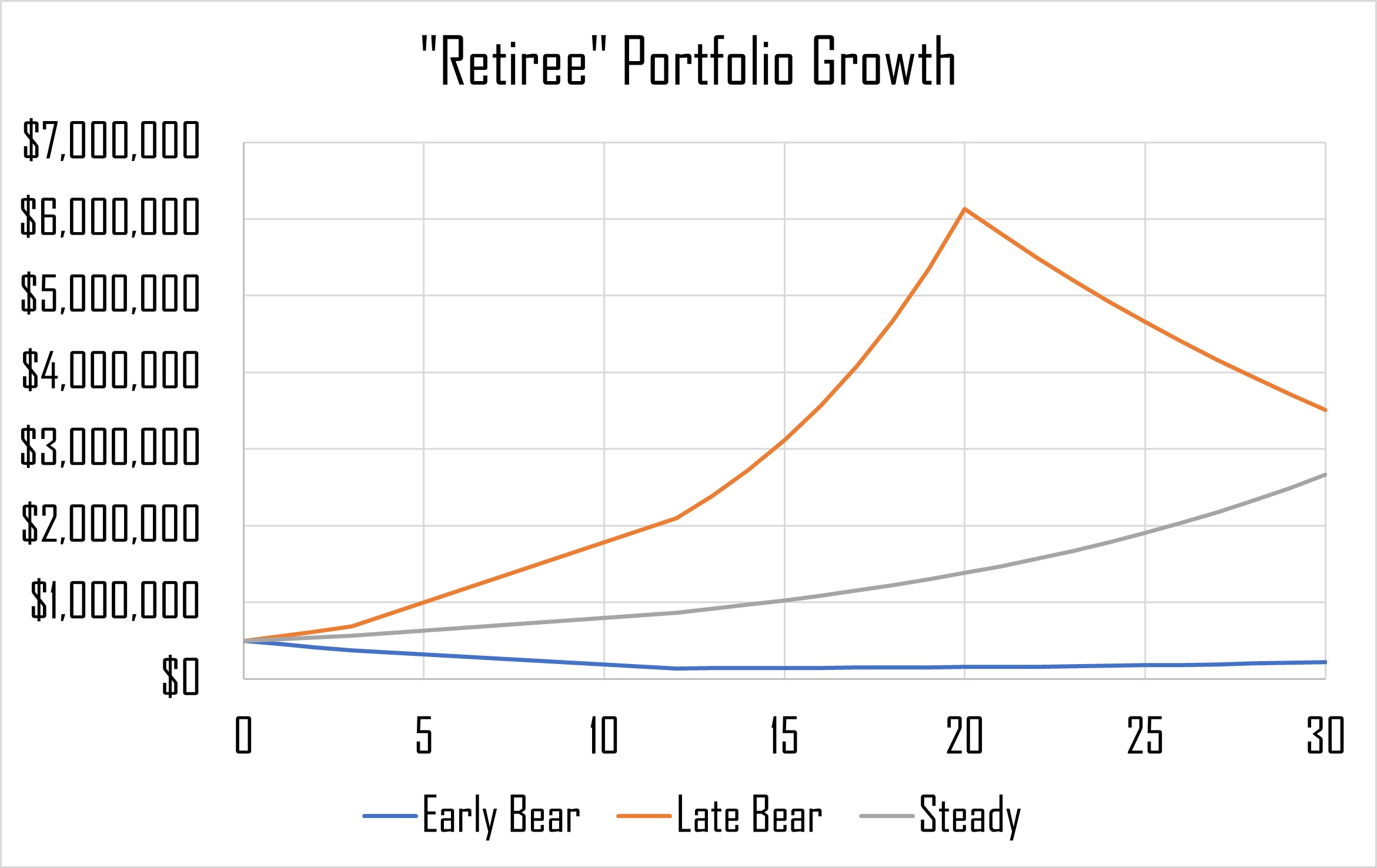

Finally, we consider the “Retiree”—this is an older individual who starts with a sizable $500,000 account balance, and immediately begins making consistent (but modest) $20,000 annual withdrawals.

For the Retiree, the relative outcomes could not be more different from those of the Saver. Here, the “Early Bear” market is almost too much to handle—the combination of market declines and principal withdrawals in the early years of retirement draws the portfolio balance low enough that even a strong market recovery can’t do much to help. The terminal account balance after 30 years is more than 90% lower than a “Steady” return would have generated.

In fact, the Retiree actually would have been better off choosing a fixed-return investment with an annual return of just 3%, instead of “chasing” a much higher (but more volatile) return.

So, what are the financial planning implications?

It can be a bit daunting to recognize that even if we know with absolute certainty what an investment’s cumulative return will be over a 30-year period, that data point alone may not be enough to provide a useful recommendation. Timing matters, and intelligent financial planning often means balancing out risks and rewards in a way that reduces variance, rather than simply chasing the “best possible” performance.

For new retirees, portfolio risk should be carefully considered, to minimize the impact of untimely bear markets. A more nimble pattern of withdrawals can also be considered, one in which distributions are higher in high-return years, but lower in lower-return years. In this case, having multiple sources of funds (or income streams) can help weather the market’s turbulence. Meanwhile, for younger investors, bear markets are not to be feared, but perhaps embraced—the sooner they come, the better. It may never “feel” right to see an account balance declining, but sometimes it’s the best thing for long-term financial outcomes. In general, the time frame that is most vulnerable to a bear market includes the 5 to 10 years preceding and following retirement. At essentially all other times, bear markets present opportunities to be exploited, not obstacles to be avoided.