Over the last several years, the ongoing debate over the relative merits of “passive” versus “active” investing has picked up steam, with the passive camp steadily gaining ground against the more traditional active portfolio managers. Lured by the simplicity and low cost of an ever-increasing number of passively-managed index funds (both mutual funds and ETFs), investors have begun to shift a significant amount of assets into passive investments, leading many industry players to begin wondering about the future of the money management industry, the structure of equity markets, and even the viability of publicly listing new stocks for sale via initial public offerings (IPOs) in an increasingly passively-managed world.

Perhaps lost amid the sometimes-hysterical conversations and debates is a simple but important point: as passive investing has grown, the lines between passive and active investing have actually begun to blur, and the distinctions between the strategies are no longer so clear. Given the confusion that remains, we thought it might be useful to define the relevant terms, to clarify the recent changes in the marketplace, and to give our view of the future of financial markets and products.

The passive vs. active debate

At its basic core, “passive” investing can essentially be defined as simply “index” investing—instead of trying to “beat” the market via active strategies (either concentrating in individual stocks, timing entry/exit points via market-timing, or other more sophisticated hedging strategies), passive investing instead simply tries to mimic the return of a benchmark index, like the S&P 500. Because index compositions are publicly known and relatively consistent, passive investing is simple and cheap for fund managers to offer, since it is basically just a basic “buy and hold” strategy—buy a basket of stocks that mimics the target index, make sure that the balance of holdings remains correct, and there is no further need for investment analysis or decisions. As a result, passive managers (like Vanguard, long the industry champion of passive investing) are able to offer their funds with much lower management fees, since no specialized manager expertise is required.

The benefits to investors have been palpable, particularly as index fund managers have become increasingly more efficient (with an assist from computerized technology), to the point that many passive funds are offered at a fraction of the cost of their actively-managed competitors—while many active funds still charge north of 1% per year in management fees, some of the leading passive funds charge less than 0.10%, and as low as 0.03%. Given that industry research has consistently shown that active management strategies, on average, provide no demonstrable or repeatable market-beating expertise, minimizing fees is one of the most reliable ways in which to enhance long-term investment returns.

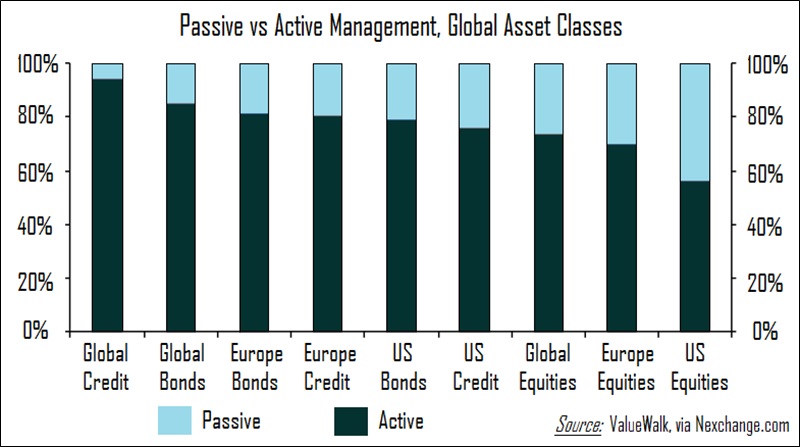

Since index investing can also offer improved tax efficiency, it should come as little surprise that a global shift from active to passive investing has occurred. According to Bloomberg data, passively managed mutual funds and ETFs saw nearly $700 billion in new-money inflows in 2017 alone, whereas actively managed funds actually lost $45 billion in assets due to withdrawals. That shift continued a decade-long trend: globally, 21.6% of investments are now passively managed, as compared to just 16.5% five years ago. If that trend continues, many industry analysts expect passive investments to outnumber active investments by 2025 at the latest.

For some, that shift comes with significant concerns: without active managers, who will be buying stocks in a market downturn? Will future bear markets become more severe as a result? And if everybody is invested in index funds, who will be left to buy a newly-listed stock that isn’t a part of an index yet? Will the entire IPO market collapse under the weight of the new passive investing behemoth?

Cutting through the hysteria

While the shift in investor preferences has been notable, we would argue that the importance of the passive surge is probably overstated, if only because the distinction between “passive” and “active” has become blurred. As passive strategies have gained popularity, the number of indexes being tracked has exploded—recent research from the Index Industry Association (IIA) finds that there are now more than 3 million recognized stock indexes in the world, as compared to only about 40,000 publicly traded companies. In a sense, then, the choice of an index is now a more “active” management decision (about 70 times more “active”) than simply picking a stock or a basket of stocks. Not all index funds are created equal, and the specific choice of index or indexes could have a larger impact on portfolio returns than a decision to use “passive” or “active” funds.

With the broadest and best-known indexes, fund choice isn’t much of an issue—S&P 500 index funds are mostly interchangeable, and the index is easy to track. That said, fund size could still matter, since some funds will be able to provide more liquidity than others in a volatile market. But in other asset classes—especially fixed income and international assets that are used to add diversification to a portfolio—the composition of the index fund matters a great deal. As just one example, “emerging markets” funds vary greatly, if only because South Korea is sometimes included as an “emerging” economy, and sometimes not. Since it is one of the world’s dozen largest economies, its inclusion (or omission) will have a great impact on subsequent investment returns. Similar dynamics occur in real estate funds, sector-specific funds, and international or “global” funds in which there is no one "standard” index benchmark. When including exposure to those asset classes, then, even the choice of a “passive” fund that tracks an index is a very “active” decision—do you choose a highly concentrated fund with 40% or more of assets in the top 2 or 3 holdings? Is the size of the fund important? What is the fund manager’s approach to rebalancing, if (and when) changes are made in the target index?

At Cypress, while we embrace the use of passive funds when constructing client portfolios, we recognize that in today’s environment, there is no such thing as purely passive portfolio management. Our fund selection process remains, at least in part, an “active” management decision, as does the risk “glide path” that we use for our clients as they age. We also make frequent tactical decisions about the relative weights of different asset classes, including the types (and maturities) of fixed income investments to include, and whether or not to incorporate currency hedges on our international holdings. Passive funds have made constructing a diversified portfolio easier and cheaper than ever before, but “active” management will never (and can never) actually disappear from the equation.