As the nation continues to recover from the ongoing shock—both economic and emotional—of the COVID pandemic, it remains to be seen how much our “new normal” will ultimately resemble our pre-pandemic lives. In addition to changes to our daily routines, our elected officials are debating a wide variety of new (or expanded) infrastructure investments, social programs, and regulatory changes, all aimed at restoring our nation’s prosperity. While there are significant disagreements on the appropriate path to take, one thing seems certain: tax laws are going to be changing, if only to help pay for some of the trillions of dollars of stimulus that have already been spent addressing COVID and its effects.

Depending on the outcome of ongoing negotiations in Washington, the changes could be either minor or major, possibly affecting corporate and individual tax rates, capital gains taxation, estate taxes, and how tax deductions and credits are calculated. Unfortunately, some of the finer tax policy nuances are lost on the majority of Americans, many of whom have only a passing knowledge of how our tax returns actually work, and what determines how much tax we all pay. So, we’ll spend some time discussing income tax basics, in hopes that everyone can better understand the potential impacts of some of the changes being discussed.

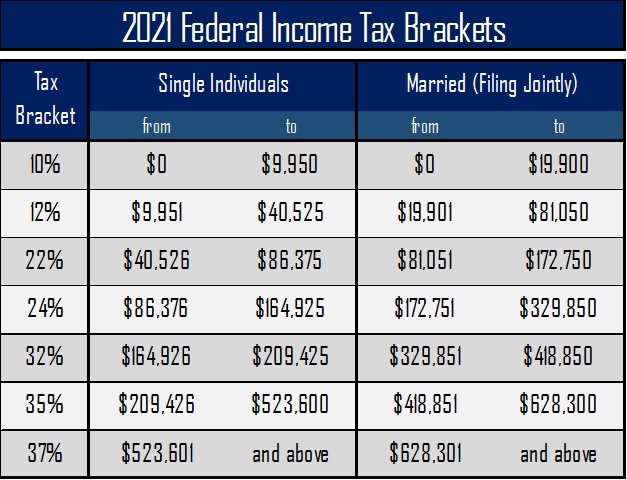

Marginal tax brackets

While most Americans have at least heard of the term “tax brackets”, not everyone perfectly understands how they actually operate. Most importantly, earning additional taxable income (and jumping up into a higher tax bracket) generally does not do anything to change the taxes owed on money previously earned. Instead, marginal tax brackets can be thought of as a series of tax “buckets”—the first pile of money goes into the 10% bucket, and that whole bucket of money is taxed at 10%. Once that bucket is full, you start to fill up the 12% tax bucket, the 22%, the 24%, and so on up to 37% (currently the top marginal tax bracket). At each inflection point, it is only the money in that “bucket”—and not the money in any of the previous buckets—that becomes subject to the higher marginal tax rate.

Source: IRS

A misunderstanding of this dynamic has unfortunately fueled a misconception among tax novices, some of whom operate under the mistaken belief that earning “too much” money can actually cause them to be worse off financially than they would have been if they had earned less. That is rarely the case, unless that extra earned income causes the taxpayer to lose eligibility for a certain tax credit or other government program. Even in those cases, though, it’s that eligibility cliff—and not the marginal tax rate structure—that causes that financial issue. Managing income can still be important—especially to minimize taxes paid in high-income years—but the benefits are almost always incremental, not earth-shattering.

Understanding deductions and credits

Beyond understanding how tax brackets operate, it is also important to recognize how tax deductions and credits are calculated, and how they impact our take-home pay. Fundamentally, there are three main categories that can impact how much of our gross income actually turns into tax owed: “above-the-line” deductions, “below-the-line” deductions, and tax credits. For deductions, “the line” is placed below Adjusted Gross Income (AGI), which is a key figure that helps determine our eligibility for a number of government programs and tax credits; “above-the-line” deductions decrease our AGI, but “below-the-line” deductions do not. Below-the-line deductions can still help us owe less income tax, but they usually do not impact eligibility for most tax credits or subsidies (like health care subsidies).

For most taxpayers, the primary above-the-line deductions are retirement plan contributions (IRA, 401-k, or similar) and HSA plan contributions. Other categories do exist (especially for self-employed individuals, or some taxpayers who pay alimony or student loan interest), but those deductions are less common. So, if you are trying to preserve eligibility for a specific program or credit, contributing money to a deferred-income retirement or HSA plan may be your only option.

Once AGI has been calculated, we then subtract either the “standard deduction” or the sum of all of our “itemized deductions” (whichever is higher) in order to arrive at our taxable income. Most things that we commonly think of as tax deductions—charitable contributions, state and local taxes (especially property taxes), mortgage interest, and some medical expenses—are in fact “itemized”, “below-the-line” deductions. Back before the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, more than 30% of taxpayers itemized their tax deductions, so these deductions were very valuable. However, beginning in 2018, that figure has plunged to about 13%. That’s because the tax reform law roughly doubled the “standard deduction” amount, which now stands at $12,550 per taxpayer ($25,100 for a married couple), while also limiting the deduction for state and local taxes (“SALT”) to a maximum of $10,000. With that SALT cap in place, very few taxpayers now have enough itemized deductions to clear that higher standard deduction threshold, which means that the actual value of all their itemizable tax deductions is essentially zero, since they no longer itemize. Contributing to charity, then, may still be an appealing prospect, but it no longer carries the same tax benefit for most people that it did pre-2017. There is some current talk in Washington of raising or repealing that $10,000 SALT cap, and that change alone could greatly impact the types (and amounts) of deductions that are available for many middle-income Americans, especially those in high-tax states.

Finally, once deductions are handled, the marginal tax brackets are applied to taxable income to calculate the amount of tax owed. It is at this point that any and all tax credits (like the child tax credit) can then be considered. Importantly, all else equal, tax credits are much more valuable than tax deductions—deductions merely reduce taxable income, so the dollar benefit is usually somewhere between 22% and 37% of the deduction. But tax credits directly reduce the actual tax owed (dollar for dollar), making them very valuable.

Other considerations

Taking a holistic view of income taxes—not just in the current year, but over a multi-decade time horizon—is often important. How should you think about capital gains taxes, and when and where to realize them? What is the value of Roth IRAs, or converting traditional retirement accounts into Roth accounts? What about estate planning considerations? All of these issues are complex and require a long-term plan, and those long-term plans could easily be upended by a bill in the coming weeks, months, or years. If you have questions about the current tax proposals and how they may impact your financial plan, we’re always happy to help provide insight wherever we can.

Information provided in this blog post is not intended to be individualized tax advice or legal advice. Please discuss such issues with a qualified tax advisor.