For more than a century, the Dow Jones Industrial Average has stood as one of the most-cited stock market indexes, captivating the attention of investment analysts and retail investors alike. But in recent years, the Dow has lost its grip over the investing public, as institutional money managers have increasingly embraced the much broader S&P 500 index. As of the end of 2020, Standard & Poor’s estimated that more than $13.5 trillion of professionally managed money (via mutual funds, ETFs, and other investing strategies) was either directly tracking or benchmarked to the S&P index, as compared to a mere $37 billion tracking the Dow (about 0.3% as much).

In 2021, that disparity turned out to be a good thing for investors, as the S&P 500 gained 26.9% for the year, comfortably beating out the Dow’s 18.7% return. The reasons for that significant performance gap stem from some basic issues with the way that the Dow is constructed, and how that methodology determines the companies that the index includes (or does not include). We’ll take some time to explain how recent market events have hurt the Dow’s performance, while also revealing some of its shortcomings as a barometer of stock market health.

Price-weighting versus cap-weighting

Most market followers are probably aware that the Dow is a relatively narrow index, comprising just 30 large blue-chip companies, as compared to 500 for the S&P 500, or more than 2,500 in the Nasdaq Composite. But what is somewhat less well understood is that the way the averages are computed are also entirely different. The simplistic Dow is a “price-weighted” index, which means that it essentially just adds the prices of the 30 constituent stocks together, and then reports the sum (the sum is actually divided by a divisor to make it an “average”, but that calculation does nothing to change the relative weightings of the companies involved). So, companies with higher share prices will always have a greater weight in—and impact on—the index than companies with lower share prices. The S&P 500, on the other hand, is a “cap-weighted” index, which means that each company is weighted based on its total market capitalization (total company value); larger companies have larger weights in the index, while smaller companies have smaller weights. The top 5 companies in the S&P 500 each have weightings of more than 2%, whereas the 5 smallest barely register 0.01% weightings.

In general, the cap-weighted approach is considered to be more reflective of “the stock market” in total, because the index will be most impacted by the stock performance of the country’s largest companies. The Dow, on the other hand, can sometimes end up with heavy weightings to companies that barely show up on the average investor’s radar (at present, UnitedHealth is the Dow’s largest component, with a weighting just south of 9%).

The impact of stock splits

If the only thing that determined a company’s per-share price was investor demand, then the difference between price-weighting and cap-weighting might not ultimately amount to much. The problem, though, is that companies can essentially set their share price wherever they want, by simply changing how many shares they offer to the public. That decision can of course first be made at the time that a company first issues shares to the public, but it can also be accomplished at any time via a stock split. In a stock split, a company will simply take all of its existing shares, and then swap them out for a pre-determined number of smaller shares—if an investor had previously owned 100 shares of a $100-per-share stock, for example, and the company decided to do a “5-for-1” stock split, that investor would subsequently own 500 shares of a $20-per-share stock. The investor’s shares would still be worth the same amount ($10,000), and the company’s total value also would not have changed. But the stock price will have been cut dramatically overnight, without any fundamental changes to the underlying business.

The reasons a company might decide to split its stock are varied, but the impact on a price-weighted index is unavoidable: the day after the stock split, the company that split its shares will only have a fraction of its previous weighting (whereas in a cap-weighted index, nothing would change). That difference can often be academic, but in August 2020, it created a massive problem for the Dow. At the time, Apple was the largest company in the world (it still is), having recently become the first $2 trillion company in history. After years of strong market performance, its share price was nearing $500, and the company decided to split its shares to reduce the price (perhaps to attract smaller investors, who could more easily buy a full share once the price was lower). A 4-for-1 stock split was announced, which immediately created a significant problem for the keepers of the Dow.

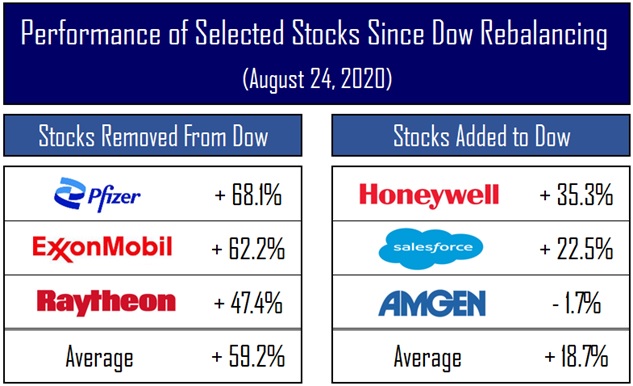

Overnight, Apple went from the highest-weighted company in the Dow (appropriate, given its size) to a pedestrian 17th, bringing its weighting from about 12% down to just 3%. As a result, the high-flying tech sector was also suddenly significantly underweight in the Dow, falling from 28% of the index to just 20% (it remained at that same 28% weighting in the S&P 500). To compensate for the “loss” of this tech weight from the Apple split, a decision was made to remove 3 of the 30 Dow stocks from the index and to replace them with 3 others, with a heavier weighting toward the technology sector. ExxonMobil—a company that had been in the Dow in some form since 1928—was jettisoned, as were Raytheon and Pfizer. They were replaced by Salesforce, Amgen, and Honeywell, each of which boasted a high share price due to a recent run of strong performance.

Unfortunately for the Dow, those stocks would soon see a reversal of fortune—since the reshuffling of the index on August 24, 2020, the 3 stocks that were removed have enjoyed an average return of 59.2%, whereas the 3 new Dow components averaged a relatively paltry 18.7% return. During that time, the S&P 500 has gained 43.1%, whereas the Dow has lagged with a 33.5% return, due in large part to the underperformance of those 3 new stocks. For what it’s worth, Apple has essentially matched the S&P 500 performance, with a 43.9% return since its stock split.

Lessons for investing

The Dow’s recent underperformance illustrates some clear limitations of the index. After all, the decision to replace three component stocks was made not due to any fundamental changes, either at Apple or at the companies in question—it was “forced” due to an overly simplistic (and perhaps outdated) method of calculating an index. The lessons for us as investors are clear—first, it is always important to understand what you own, especially in an index fund. All indexes are not created equal, and some do a better job of tracking stock market performance than others. Second, any investing strategy we devise must be flexible enough to respond to changes in the investing environment, either systemic or more localized. If our strategies are too rigid, our performance may end up suffering. Flexibility, as always, is paramount.