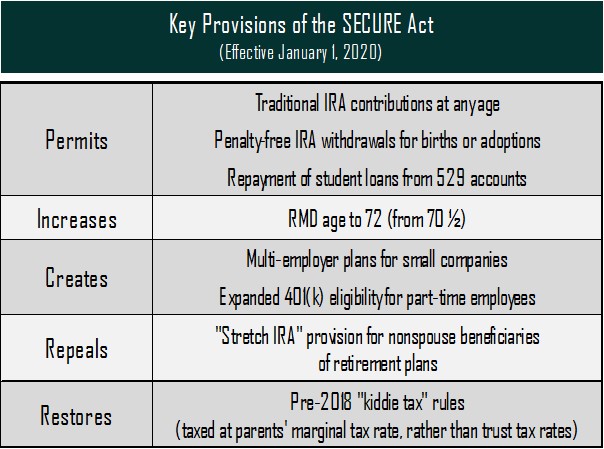

For the second time in three years, our friends in Washington have chosen to celebrate the holiday season by passing a significant tax-related bill. Two years ago, a Republican-controlled Congress enacted a substantial tax reform package, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. Then, in 2019, a divided government came together to pass a last-minute spending bill, averting what would have otherwise become the year’s second government shutdown (following a 35-day shutdown in January). While most spending bills are fairly unremarkable by nature, this particular bill became something entirely different with the attachment of the SECURE Act, a set of regulatory updates that promises to deliver the most significant overhaul of retirement account regulations since the Pension Protection Act of 2006.

We previously mentioned the SECURE Act (officially known as the Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement Act of 2019) in our Q3 newsletter last year, back when it was being debated as a standalone bill (it passed the House with broad bipartisan support, then stalled in the Senate). Now that it has officially been signed into law, it’s worth taking a closer look at the actual provisions of the rule (as passed), and what the SECURE Act might mean for you and your retirement accounts.

Updating the RMD Age

For most savers and retirees, the most significant change from the SECURE Act is the first-ever update to the so-called RMD age. Previously, anyone with a balance in a Traditional IRA (or tax-deferred 401-k account) was required by law to begin making withdrawals in the year that they turned 70 ½, with the amount determined by the individual’s life expectancy, as calculated on standard IRS tables. These Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) are a significant element of essentially every retirement plan, and understanding how they will impact taxable income (and other benefits that rely on that taxable income) can often become a central part of the retirement planning process.

Under the SECURE Act, that RMD age has now been extended to age 72, effective immediately (as of January 1, 2020). For those who turned 70 ½ in 2019 or earlier, the SECURE Act will have essentially no impact—those individuals should already be taking RMDs, and they will continue to do so on the standard schedule. But for anyone born after July 1, 1949, RMDs can now wait until the age-72 year, leaving more time for planning (and for tax-deferred growth of investments).

On a related note, the ability for older workers to contribute to Traditional IRAs has also been expanded. Prior to the passage of the SECURE Act, for older individuals who still have earned income, reaching RMD age also meant losing eligibility to contribute that income to an IRA (once RMDs started, contributions had to end). That limitation has been removed entirely, with no maximum age for Traditional IRA contributions. Again, this change is only valid for individuals born after July 1, 1949 (and only matters for individuals who still have earned income).

Finally, for individuals who are inclined toward charitable giving, it bears mentioning that the age at which Qualified Charitable Distributions (QCDs) can begin remains unchanged at 70 ½, and is not affected by the update to the RMD age.

Say goodbye to the Stretch IRA

Now, for the bad news. In order to help “pay” for the costs of extending the RMD age, the SECURE Act has also eliminated the “Stretch IRA”, effective immediately. Under previous law, nonspouse beneficiaries (usually either children or grandchildren) of retirement account owners were allowed to spread out distributions from those accounts over their own life expectancy, rather than that of the decedent. That preferential treatment often allowed for a substantial amount of additional tax-advantaged growth, over the course of several decades. But under the SECURE Act, all inherited retirement account balances must be distributed in full within 10 years of the original account owner’s death. There is no set schedule for distributions to take place, but the concern for inheriting beneficiaries is twofold—not only must all of the tax on these accounts be paid much sooner than in the past, but the tax rate on those accelerated distributions will also likely be much higher than under previous law, since these distributions are likely to be bunched into the peak earnings years of the beneficiaries (years in which marginal tax rates are already high).

For individuals who are planning to leave substantial retirement account balances to the next generation, this rule change represents a significant challenge, threatening to turn the traditional wisdom of contributing to a tax-deferred retirement account on its head. Both retirement planning and estate planning conversations now must include a new level of nuance: when considering which assets to spend (and which to leave to heirs, and what to leave to whom), some knowledge of the relative income levels—and marginal tax rates—of those beneficiaries should ideally be incorporated into the analysis.

For example, if an older individual expects to pass away with some tax-deferred retirement accounts, but also some non-retirement assets (house, brokerage accounts, business interests, etc.), then it may now be optimal to leave the retirement accounts to a lower-income heir, and the other assets to someone whose income (and tax rates) are higher.

In certain cases, it may even be optimal to accelerate distributions from the account during the life of the original account owner, potentially via a partial Roth conversion or other tax-sensitive maneuver.

Other provisions of the law

While the RMD update and the Stretch IRA repeal will be the most important provisions of the Act, there are other smaller items of note. It will now be easier for part-time employees and small businesses to establish (and contribute to) 401(k) plans, and annuities will also be more readily available in retirement plans (which may or may not be a good thing).

Penalty-free withdrawals are also now available to cover certain birth or adoption expenses, and there has also been a beneficial update to the Kiddie Tax rules, repealing a change that had been made under the 2017 tax reform law. If you have questions about how the SECURE Act impacts your retirement plan (or estate plan), we at Cypress are happy to help, as usual.