The first half of 2022 has been extremely challenging for markets and investors of all types, generating numerous attention-grabbing statistics and headlines along the way. Depending on your chosen metric, the past two quarters have been among the worst in more than 30, 40, or even 50 years of market history, yielding comparisons to some of the bleakest American economic periods.

In many ways, those historical analogies are justifiable, but we’d like to step back from the doom and gloom of today’s headlines and take more of a big-picture view of what it means to be an investor, and what our expectations (and goals) should be.

Why we invest

During times of market stress, it can sometimes be important to remember that just having excess cash available as “savings” is a luxury few can afford. Even in the United States—one of the wealthiest nations in the world—only about half of adults have more than 3 months’ worth of expenses accumulated in savings, and fewer still have any appreciable assets to invest in the markets. For many, the gyrations of the stock market are a mere side note, and have no appreciable impact on their daily lives, either now or in the future.

The relative luxury of possessing accumulated savings also comes with some level of risk, by definition—if you choose not to invest at all (the “keep it under my mattress” option), then you are accepting by default a gradual decrease in purchasing power, as the compounding impact of inflation erodes the value of your hard-earned dollars. “Cash” might not feel like a conscious investment decision, but it is—there may not be any direct investment-related risk, but the risk of inflation cannot be avoided without taking some further action.

That “further action” can take many forms, from purchasing real estate to investing in savings bonds, private companies, the stock market, or perhaps all of the above. In general, with all investments, there is a trade-off between safety (return of capital) and investment gains (return on capital), and to consistently match or beat inflation over the long run, at least some investment risk must be accepted.

But how we choose to define our “investment risk” can be a complicated problem, and determining how “safe” or “risky” a certain investment will be often requires some level of guesswork. That guesswork becomes ever more meaningful on shorter time periods—we may have a high degree of confidence of the potential returns on a given investment over a 10-year period, but have little to no idea what that same investment will do next week, next month, or even next year.

Consider, for example, the two broadest categories of investment assets, stocks and bonds. Over long periods, the U.S. stock market has produced an average annual return of roughly 10%, whereas high-quality U.S. Treasury bonds have produced about half the return, just above 5% on average. Why, then, would any investor bother to invest in bonds? The answer lies in the variability of those returns, and how predictable they may be from one year to the next.

Treasury bonds do not often experience negative returns over the course of a calendar year, and when they do, the declines tend to be manageable—only once in the last 50 years have U.S. government securities lost more than 10% in a calendar year, and that decline came in 2009, at the peak of the financial crisis. Even then, those losses were recovered within 18 months, as interest rates quickly normalized and markets stabilized.

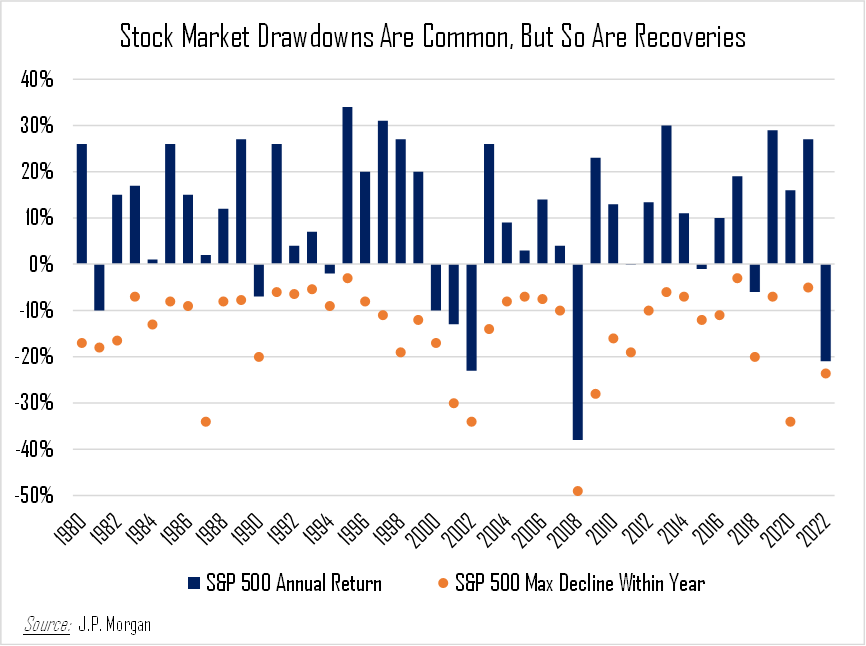

Stocks, on the other hand, frequently see these sorts of declines. In fact, since 1980, the average intra-year decline (as measured from “peak to trough”) for the S&P 500 is 14%, even though stocks ultimately finished the year in positive territory in 32 of those 42 calendar years. Bumpy rides are the norm in the stock market, and that volatility (and the frayed nerves that come with it) is the price to be paid for higher long-term returns.

Investing lessons from history

Turning back the clock to 1979, financial conditions in the United States were in many ways similar to the present day. The stock market was struggling, geopolitical tensions were high, and the long-term health of the global economy was in serious doubt, with inflation running rampant amid an ongoing energy crisis, leading to persistently high interest rates and stagnant economic growth. In August of that year, BusinessWeek ran a cover story titled “The Death of Equities”, arguing that stocks were no longer a compelling investment option, and that long-term investors should turn their attention elsewhere.

As it turns out, the timing of that article could not have been more ironic. The next two decades proved to be among the most prosperous periods in stock market history, generating an average annual return of more than 18%, nearly double the long-term average. Sometimes it is on the days that seem the darkest that the best investment opportunities arise; it’s important that we maintain that long-term perspective, especially when our portfolios are struggling.

Take, for example, the experience of just two years ago, during the initial onset of the COVID pandemic in 2020. From February to March, the S&P 500 dropped by more than 33%, including two dramatic daily declines of more than 10% as the seriousness of the situation quickly became apparent. Financial markets of all types seized up as economic activity came to a screeching halt, with lockdowns and other restrictions becoming increasingly more stringent. Investor fear was palpable, but the stock market actually bottomed much sooner than anyone could have anticipated—on Monday, March 23rd, just a week into the initial “15 days to slow the spread” window, the S&P began a significant bounceback rally. Within a month, stocks had gained back 25%, and while it would take until August to fully recover the initial losses, that March 2020 turning point launched a rally that would last 18 months, during which time the major indexes more than doubled.

In 2020 as in 1979, the difficulty of “timing the market” was on full display. Investors of all types—including seasoned professionals—tend to be vulnerable to recency bias, which is the expectation that the future will look just like the recent past. They therefore tend to sell when stocks have been going down, and buy when they’ve been going up, eating into their long-term returns as a result. As long-term investors, we must recognize that achieving positive long-term returns means accepting periods of uncertainty and discomfort, some of which are easier to stomach than others. Instead of focusing on where our portfolio values used to be, we should focus on where they are (or may be) heading, and focusing on the opportunities that these difficult periods present.