In late August, just two weeks after the Inflation Reduction Act passed on a party-line vote, President Biden announced a controversial student loan debt forgiveness program, promising what the administration calls “targeted cancellation” of federal student loans for qualified borrowers. Intended mostly for lower-income individuals, the plan’s major provisions are projected to cost anywhere between $400 billion up to nearly $1 trillion over the coming decades, making it one of the largest financial commitments of the Biden era.

There is still substantial uncertainty surrounding the plan, with many details remaining fuzzy and at least two pending lawsuits further muddying the picture. Nevertheless, we think it’s worth taking some time to sift through the details of the pending program, to help affected individuals understand their options while also providing some context to the broader student loan issue.

Understanding the student loan landscape

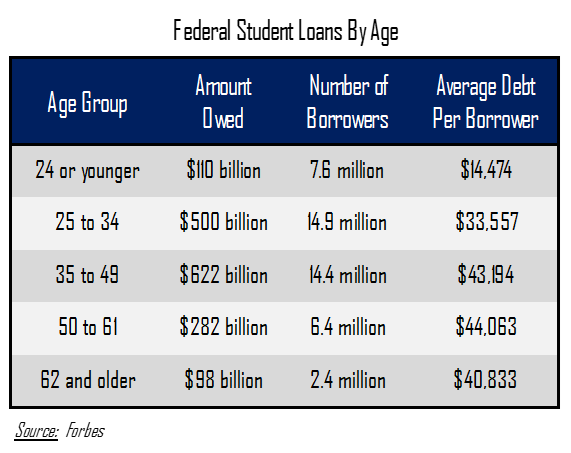

With college tuition costs marching ever higher in recent years (annual tuition inflation exceeded 6% between 1977 and 2022, more than doubling the broader inflation rate), student loan balances have ballooned. That growth in costs has begun to slow somewhat, but the accumulated figures are substantial: one in five households now carries at least some student debt, and total outstanding debt is now roughly $1.7 trillion, having nearly doubled over the last decade alone. That amount dwarfs the total level of consumer credit card debt, which is currently less than $900 billion. Student loan debt is unique among consumer debt, in that it is not dischargeable in bankruptcy, regardless of who issued the loans. Aggressive collection methods can apply, including wage garnishment, suspension of professional licenses, forfeiture of Social Security income, withholding of tax refunds, and more.

While student loan balances are clearly concentrated among younger folks, they do impact older generations as well, either stemming from their own advanced degrees or from borrowings on behalf of their offspring or other family members. And while salaries for college graduates are usually high enough to service those debt balances, it’s clear that the loans are beginning to impact the financial decisions of the younger cohort. Studies have repeatedly shown that millennials are delaying marriage, shunning home ownership, and having children at increasingly advanced ages. Financial stresses from student loan debt cannot entirely explain all of those issues, but they are likely a contributing factor.

Efforts to reduce or eliminate any portion of this debt have sparked a significant amount of controversy, and with good reason. Issues of equity and fairness are considerable, especially for graduates who have already worked for years to repay their loans, or for taxpayers who never attended college. Less than 40% of American citizens have obtained a college degree, so that divide is far from trivial. Perhaps more importantly, forgiving existing loans does nothing to address the underlying problem of rising costs; it’s actually more likely to exacerbate the problem, since ongoing subsidies will naturally create perverse incentives. The timing of the proposed forgiveness is also difficult to defend, with rampant inflation already proving to be difficult to address. Adding to the deficit in this environment seems ill-advised, and it could force the Fed to hike rates even higher in order to counter any additional inflation stemming from the forgiveness.

What the program does

As mentioned above, there is still substantial uncertainty surrounding the proposed program. First, the timeline is still unknown—the administration hopes to have the basic infrastructure in place before the end of the year (perhaps as soon as October), but it’s still unclear what that timeline means, or how things will actually be administered. Second, legal challenges have already been launched, mostly surrounding the legality of granting this level of forgiveness without congressional approval (as of now, the program relies on an executive order). That uncertainty is further highlighted by the pending midterm elections, which could shift the political landscape in a way that slows or halts the program’s rollout. Still, the broad strokes of the plan have been laid out, and forgiveness seems likely to proceed in at least some form.

The first phase of the plan is already in effect, simply representing another extension of a repayment pause. All federal student loans were placed in forbearance at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, and that forbearance has now been extended for a seventh time, through the end of 2022. Federal borrowers have not been required to make a payment since March 2020, a period that now exceeds 30 months.

The second phase is the “targeted cancellation”, which is the aspect that has generated the vast majority of the attention thus far. Federal student loan borrowers with less than $125,000 of annual income ($250,000 for married-filing-jointly) will qualify for $10,000 of debt cancellation, while borrowers with Pell Grants can qualify for an additional $10,000. Roughly 43 million Americans have federal student loan debt, and the White House expects that the plan will completely eliminate the balances for 20 million of them.

Finally, both current and future borrowers can benefit from a significant expansion of the existing income-based repayment (IBR) program. Under current guidelines, borrowers on IBR plans who pay at least 10% of “discretionary income” toward their loan balances can have any remaining balance wiped out entirely after 20 years, as long as they continually made “qualified payments”. The Biden plan proposes to drop that threshold to 5%, while also redefining “discretionary income” in a way that could make some borrowers owe essentially nothing. The IBR portion of the plan currently carries the most uncertainty, and it could also prove to be the most costly aspect, depending on how terms are defined and on how schools and borrowers respond to the new rules.

Debt cancellation applies to loans disbursed before June 30, 2022, and income limits should be based on either 2020 or 2021 tax returns. Loans paid off before the onset of the pandemic will not be eligible for forgiveness; it is unclear what will happen for the small portion of borrowers who may have paid off their balances during the pandemic. Parent PLUS loans and graduate school loans will qualify, but Perkins, FFEL, and private loans generally will not. Some states intend to tax debt cancellation at the state level, which could complicate matters for residents of those states.

Setting the significant political issues aside, if executed well, a decrease in student loan debt burden could fuel a surge of investment into retirement accounts, homeownership, or a number of other productive economic uses. The timing of the forgiveness is still questionable, but the net economic benefit could still be very positive, if the plan ultimately survives.