As both short-term interest rates and 30-year mortgage rates continue to edge higher, homeowners are beginning to question anew the relative benefits of paying down mortgage debt versus setting aside their excess cash for other purposes. Determining “the right amount” of mortgage debt to hold is a complicated decision, and the answer is not usually static—it can change as circumstances change, either in the broader economy or in the narrower scope of a family’s evolving financial picture.

Trying to navigate that intersection of personal circumstances and current economic opportunities is what we do best at Cypress, so we’ll try to lay out some of the considerations at play in making (or reconsidering) such a decision.

The (investment) opportunity cost

Any decision about paying down debt begins with a consideration of the opportunity cost for that cash—in other words, if you didn’t choose to pay down debt, what would you be doing with that money instead, and how much would that alternative option be worth to you? More often than not, this decision requires nothing more than a simple comparison of the existing mortgage rate versus the expected return on other investments—if your mortgage is at 3.5%, but you think you can reliably earn 6% annually in an investment account, then paying down debt doesn’t seem worth it, since you could earn more in investment returns than you’d be saving in interest by paying down the mortgage. But if your expectations for investment returns are lower (or your mortgage rate is higher), then the decision could shift. In that sense, then, the decision can (and should) be different for different people, if only based on an individual’s investment risk tolerance. Higher returns almost always correlate with higher risk-taking, so an investor with a low risk tolerance is less likely to clear the mortgage rate “hurdle” than another individual with a more aggressive approach.

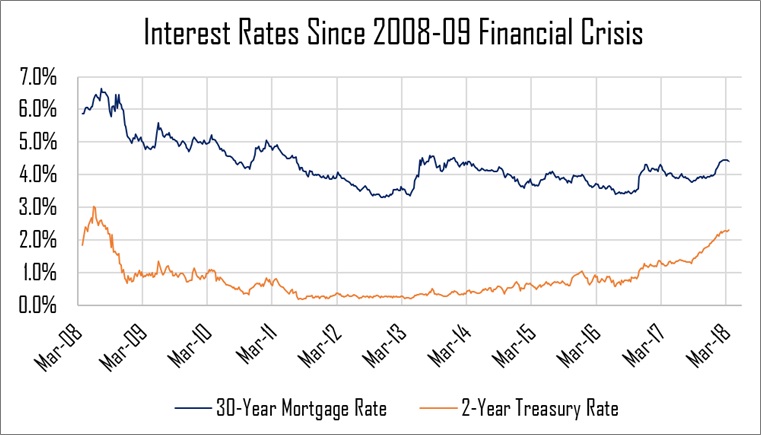

The calculations can also change over time, as investment opportunities evolve. When shorter-term interest rates were at or near zero for several years, there was almost no chance of beating out the return on a mortgage repayment without accepting a relatively large amount of risk (and remember, the “return” on interest savings from paying down debt is always fixed and knowable, and thus “guaranteed”), so retiring debt seemed attractive in relative terms. But now that those rates are starting to tick higher, that math is changing, and less risk is required in order to beat the mortgage hurdle. Arguably, now is the least beneficial time to pay down mortgage debt in at least 10 years, at least for lower-risk investors who aren’t keen on adding additional stock market risk to their portfolios.

Of course, taxes can also come into play in this decision, as with most financial planning decisions. One of the major benefits of mortgage debt is that interest on a primary mortgage is typically tax-deductible, at least up to a certain threshold (now $750,000 of mortgage debt under the new tax reform law, down from $1,000,000 previously). That tends to drive the “effective rate” of mortgage debt below its stated rate, due to the tax deduction. Paying down a mortgage, then, doesn’t necessarily generate a “return” of the full mortgage rate; the net benefit can be offset by increased taxes. In that regard, the benefit of retiring mortgage debt is theoretically less valuable the higher your income. Note, though, that the tax benefit only exists for individuals who itemize deductions, which may be many fewer now that tax reform has greatly increased the standard deduction.

But the alternatives may come with tax consequences as well, especially if investing in a taxable account (as opposed to a tax-advantaged retirement account). Taxable accounts, 401(k) accounts, Roth IRAs, 529s, and other vehicles all come with different sets of tax assumptions, and the comparison of rates can be more complicated than a first-blush analysis might suggest. A taxable account investor who takes the standard deduction on his tax return will, all else equal, see more of a relative benefit from retiring mortgage debt than, for example, a Roth IRA investor who itemizes.

The interplay between these variables—risk tolerance, tax status, and more—means that personal circumstances are often at least as important as broader economic factors.

The (non-investment) opportunity cost

The previous analysis, though, assumes that the only two options available to an individual are to pay down a mortgage or to contribute to an investment portfolio. In reality, the options are rarely so limited. For one, mortgage debt isn’t always the only type of debt on a household’s balance sheet: student loan debt, auto loan debt, credit card debt, and even 401(k) plan loans all have different interest rates, and also different tax implications (student loan debt, for example, enjoys a tax deduction for up to $2,500 of interest, but that deduction is subject to an income limit); mortgage debt may not be the highest priority.

Source: St Louis Fed (FRED)

In addition, the availability of an employer matching contribution in a 401(k) plan might impact the best use of any excess cash. In general, as financial planners, we tend not to recommend aggressive debt retirement unless and until two conditions are met: 1) sufficient liquid cash exists in an “emergency fund”, and 2) any employer match in a workplace retirement plan has been maximized. Once cash has been used to retire debt, it isn’t always easy (or even possible) to get that cash back if it’s needed for other purposes. That’s especially the case with mortgage debt, where freeing up cash will require either a refinancing of the mortgage or a separate home equity loan (which, again, due to tax reform, no longer enjoys the same tax benefits as initial-purchase mortgage debt).

Other considerations

From a budgetary standpoint, it’s important to remember that as a general rule, overpayments to a mortgage will not impact the monthly payment, but will instead simply decrease the remaining loan term. If an annual household budget is tight—or is likely to become tight due to an expected career change or increased expenses—then it’s important to choose the proper size mortgage before the loan is taken out. To change the monthly payment after the initial loan underwriting could be costly, and fluctuations in interest rates might make refinancing uneconomical. One industry rule of thumb is never to exceed 200% of annual income in mortgage debt, but that’s at best a blunt tool. At Cypress, we’re always happy to help our clients consider the relative costs and benefits of different debt management strategies, both for existing mortgages and for new loans. Debt can be a very useful tool, but knowing how and when to use it well is an important skill in meeting long-term goals.