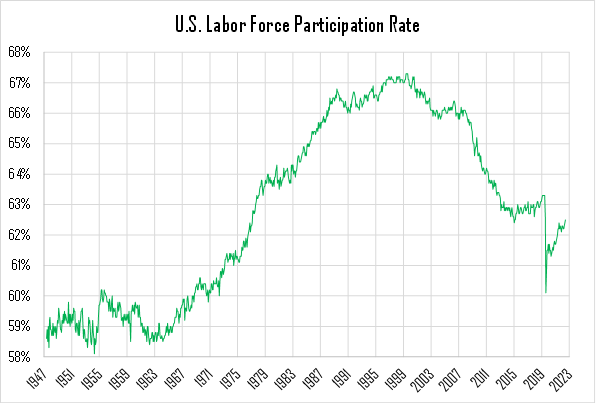

The persistent inflation that has plagued the global economy over the last two years has had multiple causes and phases. First, as COVID lockdowns were lifted, jammed-up shipping ports led to a frozen supply chain, which made many products scarce and essentially unavailable. Those supply chain concerns have now largely eased—shipping costs and lead times are now back to prepandemic levels—but other disruptions persist. One of the most notable legacies of the pandemic era is a significant decline in the total labor force participation rate, making labor shortages both commonplace and difficult to address.

The supply-and-demand mismatch in the labor market began with a wave of premature retirements among workers in their late 50s and early 60s, many of whom might otherwise have remained in the workforce for several more years. This caused the national labor force participation rate to plummet from above 63% to barely 60%, representing several million “missing” workers. Those retirees have been difficult to replace, and their absence caused upward pressure on wages, thus fueling another bout of inflation.

Thankfully, reinforcements are finally beginning to arrive, due in part to increases in layoffs and voluntary resignations. At one point last fall, there were nearly two job openings for each unemployed person, a record level. As labor force participation has crept back toward prepandemic levels, the ratio has eased lower, but it remains exceptionally high. That labor market tightness will continue to add fuel to inflationary pressures, although it could also help to soften the blow of any impending recession.