For decades, Social Security benefits have stood as a linchpin of any properly designed retirement plan. Originally conceived during the Great Depression as a national pension “safety net”, the system remains important for the vast majority of retired workers. More than 50 million Americans currently receive Social Security retirement benefits, and nearly 40% of those beneficiaries receive at least half of their income from the program, with retirees receiving average benefits of roughly $1,800 per month.

Unfortunately, in recent years, the Social Security Administration’s finances have gradually deteriorated, and the long-term solvency of the program has become the topic of near-constant media attention. Most recently, this spring, the Trustees of the Social Security trust fund issued an annual report stating that they projected their trust funds to be entirely depleted by the end of 2033, a report that was immediately picked up and shared by nearly every national media outlet. But what is the Social Security trust fund? And what happens if (or when) it runs out of money? Should we be concerned, or panic? Is immediate action required? We’ll spend some time to understand the background of the program, how we got here, and what the future may hold.

Understanding the Social Security trust fund

At its core, Social Security is a pay-as-you-go system, meaning that current workers pay taxes into the program, which are then immediately passed through to pay out benefits to current retirees. When those current workers grow old and retire, the new generation of workers that replaced them pays their own taxes, which then “repays” the retirees for the money they put into the system over the years. Of course, there is not always a perfect balance between the working-age population and the retired population—in years when there is more money going into the system than is flowing out to retirees, the excess is swept into a “trust fund”, which then accumulates and earns interest (from so-called “special-issue securities” issued directly by the U.S. Treasury) until the demographic picture shifts, at which point those accumulated funds can be used to cover any shortfall in revenues.

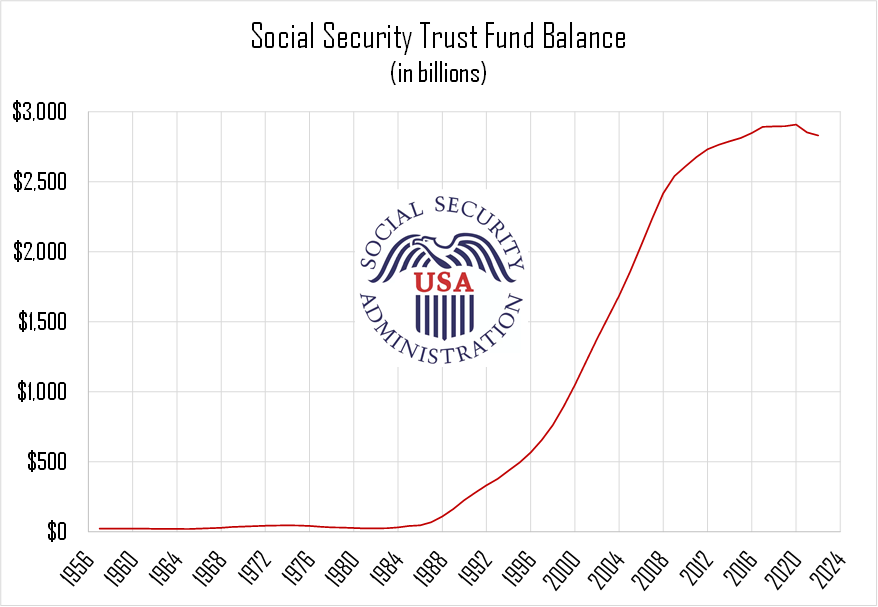

For nearly four decades, a robust work force and a steadily growing economy meant that more money was being paid into Social Security than was being paid out; indeed, for every year between 1982 and 2020, money was deposited into the trust fund, which reached a level of nearly $3 trillion at its highest point. 2021 and 2022 marked the first years of trust fund drawdowns in nearly 40 years, as pandemic-era distortions mixed with an acceleration in Baby Boomer retirement rates fueled a decrease of about $75 billion over 2 years ($55 billion in 2021, but then only $20 billion in 2022 as pandemic restrictions eased and the economy returned to “normal”).

But the trust fund still boasts more than $2.8 trillion in assets today, which gives the program more than enough room to maneuver, given that incoming taxes still cover the vast majority of annual benefits paid. The program, on the whole, is much healthier than is typically let on, despite numerous breathless headlines (and politician soundbites) to the contrary. Still, the impact of demographics cannot be ignored, and the outlook for the future is problematic. The national fertility rate has steadily declined, and now stands at a level of about 1.8 births per female, which is below the population “replacement level” and has been for more than a decade. By contrast, the fertility rate stood consistently above 3.0 for every year between 1950 and 1965. So, today, there are fewer new workers aging into the work force, at the same time that an increasing number of retirees are leaving it. As a result, the rate of bleed from the trust fund is projected to accelerate significantly over the next several years, especially if economic growth stays low, labor force participation remains stagnant, and life expectancy of retirees remains high. In 2020, 17% of the population was over age 65, a figure that is expected to grow to above 24% by 2060, creating a demographic puzzle.

Even if the trust fund is indeed depleted by 2033, though, this does not mean that Social Security becomes bankrupt, or that benefits will cease being paid. Even under the Trustees’ conservative projections, incoming tax revenues will still cover at least 77% of promised benefits, even without any legislative changes. There is plenty of time to close that gap, and even some fairly minor changes can have a significant long-term impact.

Summarizing potential changes to the program

Contrary to popular misconception, then, the exhaustion of the trust fund does not mean the end of the program, or the bankruptcy of the entire system. The 2033 deadline, such as it is, is simply a date by which “something must be done” in order to keep paying benefits at their current (“promised”) levels. So, what can be done?

Since policymakers have been aware of this impending demographic challenge for at least 20 years, there is no shortage of proposals for the best way (or ways) to fix the issue. Indeed, a recent study from the Trustees identified more than 120 unique policy tweaks that could potentially extend the solvency of the trust fund, perhaps as long as another 60 to 70 years. Those proposals generally fall into three categories: changes to cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs), changes to the full retirement age, and changes to taxation structures. In reality, a combined approach is likely to be required, but changes to COLAs alone can likely make up a large part of the difference. Social Security benefits, then, could continue to be paid as scheduled, but their growth over time might not quite keep pace with real-world inflation. Further extending the retirement age is another potential option, as has already been done in the past. The Social Security “Full Retirement Age” started at 65 for those born in 1937 or earlier, extended to 66 for those born between 1943 and 1954, and now maxes out at 67 for those born after 1960. An extension to 68 or 69 for younger retirees would seem to be a logical extension of past policy decisions.

Finally, multiple changes to taxation could be considered. The Social Security tax rate may not change, but the wage base cap (the maximum level of wages above which Social Security taxes are no longer owed) could be increased, as it was in 1977. There could also be changes to taxation of Social Security benefits, but that is likely to be less politically popular. More extreme options (like investing the trust fund in stocks, for example) could be considered, but there is a lot of wiggle room left before we get to that point.

Other considerations

These sorts of solvency crises have come up before—most notably in 1977 and 1983—and Congress has consistently acted to extend the program’s viability. We expect them to do so again, but in the meantime, Social Security is likely to be used liberally as a political football. At Cypress, we speak often with our clients about Social Security claiming strategies, and while the long-term solvency of the program is a consideration, the crisis level is nowhere near as severe as the public discourse would suggest. We encourage all potential Social Security beneficiaries to make decisions based on data and analysis, not fear-mongering.