With supply chain strains exacerbating by the day and labor market tightness persisting, inflation is on the minds of investors and economists everywhere, as the global economy tries to find a "new normal" in a post-pandemic world. Until recently, most analysts expected that the above-average inflation rates from this spring were temporary, the symptom of a stagnant economy suddenly spurting back to life. But now even Federal Reserve officials are conceding that inflation trends are unlikely to be simply "transitory", and that the pressures could take several more months—if not a couple of years—to ease.

But even if the current fears prove to be overblown, and price trends do quickly moderate (as an old commodity-market saying goes, "the cure for high prices is high prices"), I'd argue that inflation should always play an important role in our investing decisions, albeit in a much different manner than that to which we've recently become accustomed. After all, the goal of any investing approach should be to help meet future financial needs, and any estimate of "future financial needs" must (by definition) include some assumption regarding long-term inflation rates. If we don't have a view on future inflation trends, then it's nearly impossible for us to project how much money we'll eventually need, and thus, how much of an investment return we require (or should be seeking) on our portfolio.

And ultimately, regardless of current market conditions or individual risk tolerances, it's that required return that should really be the focus of our investing strategies. Forget about how much of a return we think we can (or "should") earn; a more important question is how much of a return do we need to earn in order to meet our various financial goals? And once we've determined that required return figure, is it an achievable number, or not?

As we endeavor to calculate that required return, it's important to note that "inflation" is, in fact, a very personal statistic. No matter how many economists or Fed officials try to convince us that inflation is a calculable figure that can be determined down to the hundredth of a percentage point, the reality is quite different. On the contrary, there is no single inflation rate that applies to all investors, but rather hundreds or thousands of unique rates across the country. And to the degree that those inflation rates vary from person to person, so too will those investors' required returns, all else being equal.

Consider two recently-retired investors, both of whom have the same retirement account balances and the same annual expenses. One of them, though, expects an annual inflation rate of 1% during his retirement years, while the other expects inflation of 3%. Should those two investors have the same portfolio strategy, accepting the same levels of investment risk? Almost certainly not, and yet as often as not, their portfolios will end up being nearly identical, at least from a risk perspective ("100 minus your age", and so forth).

The fact is, just determining your own risk tolerance is insufficient to determine an appropriate portfolio strategy. Measures of risk capacity (and risk requirement) are also necessary in order to ensure that undue risk is not being accepted. And in order to determine that risk capacity, a full understanding of the factors that can impact your personal inflation rate is vital.

It's not enough to simply consider a catch-all inflation rate and to assume that it will apply to you and your financial situation. Understanding your own budget—and how it is likely to change over time—is an essential step in building an appropriate portfolio. Here are some of the factors that you should be considering.

Geography

Our nation is a large one—the third-largest in the world both by area and by population—and that size brings with it a significant amount of regional variation. These regional differences can yield a wide variety of differences in spending patterns, from eating habits to exercise habits to choices in entertainment options, and more. Even differences in climate can have a dramatic impact on the way we spend our dollars—the price of heating oil matters a great deal in New Hampshire, but it may not be too relevant in Arizona.

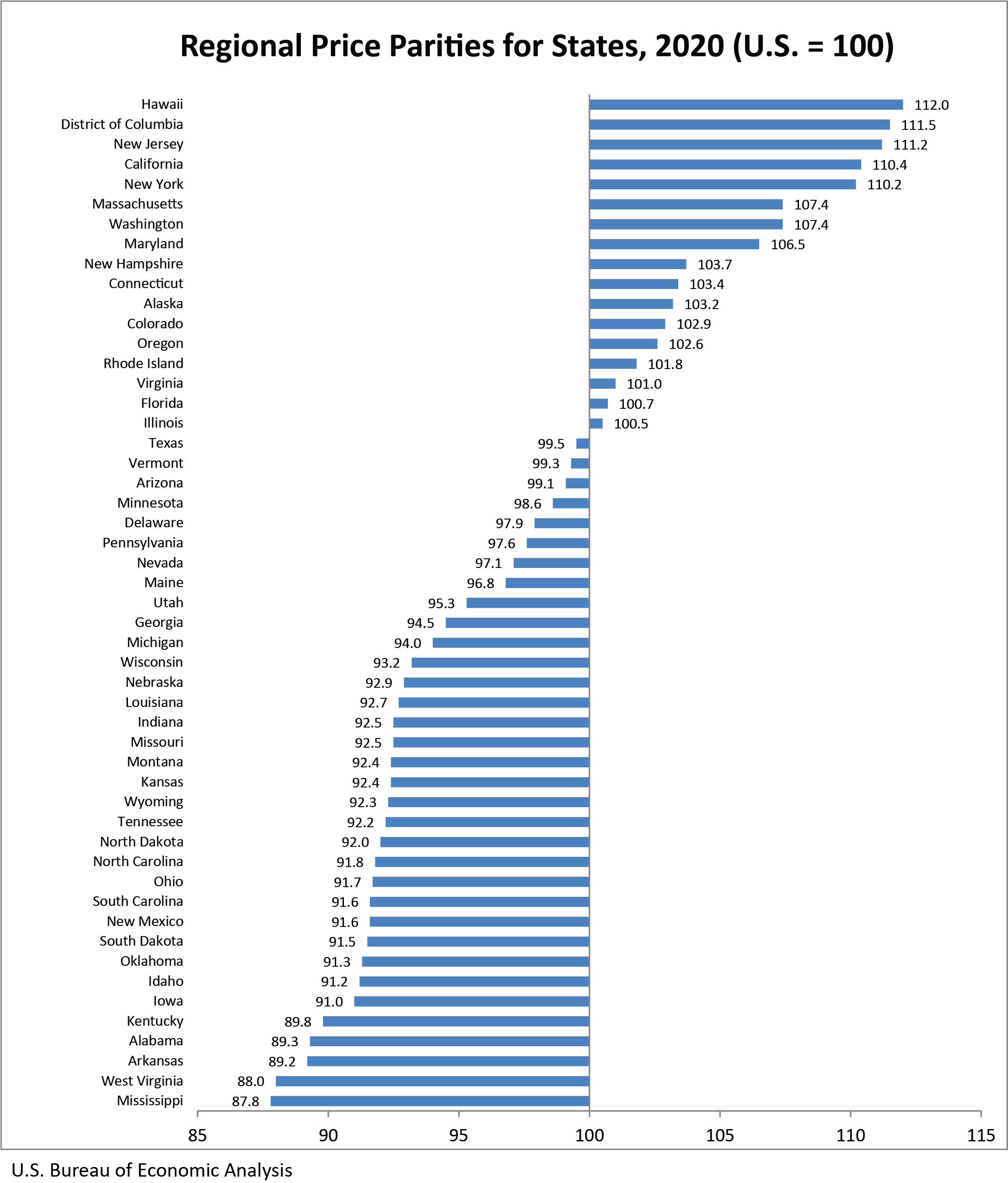

The inflation-watchers at various federal agencies do try to account for these geographical differences by generating a number of regional and city-specific inflation measures, but those figures don't draw nearly as much attention as the national summary statistic, nor do they tend to guide monetary policy decisions. But from a financial planning perspective, they can be vital; the Bureau of Economic Analysis produces a periodic chart to compare relative price levels by state, a dynamic that was discussed a few years ago by Stanford economist John Cochrane:

As Cochrane pointed out, the difference in cost of living between (for example) Mississippi and California is significant enough that they might as well be entirely different economies (or at least, using entirely different currencies). And that difference can apply not just to the current cost of living, but to trends in inflation as well. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), as of November, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) in the Atlanta area increased by a robust 7.9% year over year, whereas the Boston area clocked in at a more modest 5.3% growth rate (still high, but significantly lower).

In other words, differences in cost of living are wide and growing, and those who are saving (and investing) for retirement should take note. National averages might as well be meaningless; local trends are all that matter when it comes to your personal budget and your projected financial needs.

Age

Another issue with the catch-all inflation rate is that it assumes a constant "basket" of goods and services, when in reality, our consumption trends naturally change over time. As we get older, we might choose to travel less and spend less (or maybe more) on restaurant meals. We'll also most likely buy less new clothing, and we'll generally settle into a more stable housing situation; our direct housing costs may even approach zero if and when we pay off our mortgages.

But the most important change in our spending patterns as we age is our consumption of health care services—by some measures, more than half of our lifetime medical expenses are incurred during our retirement years, more if we are unlucky enough to experience a major illness or injury. And since medical costs have been outpacing inflation for decades now, that dynamic alone will cause effective inflation rates for the elderly to be higher than those for middle-aged individuals.

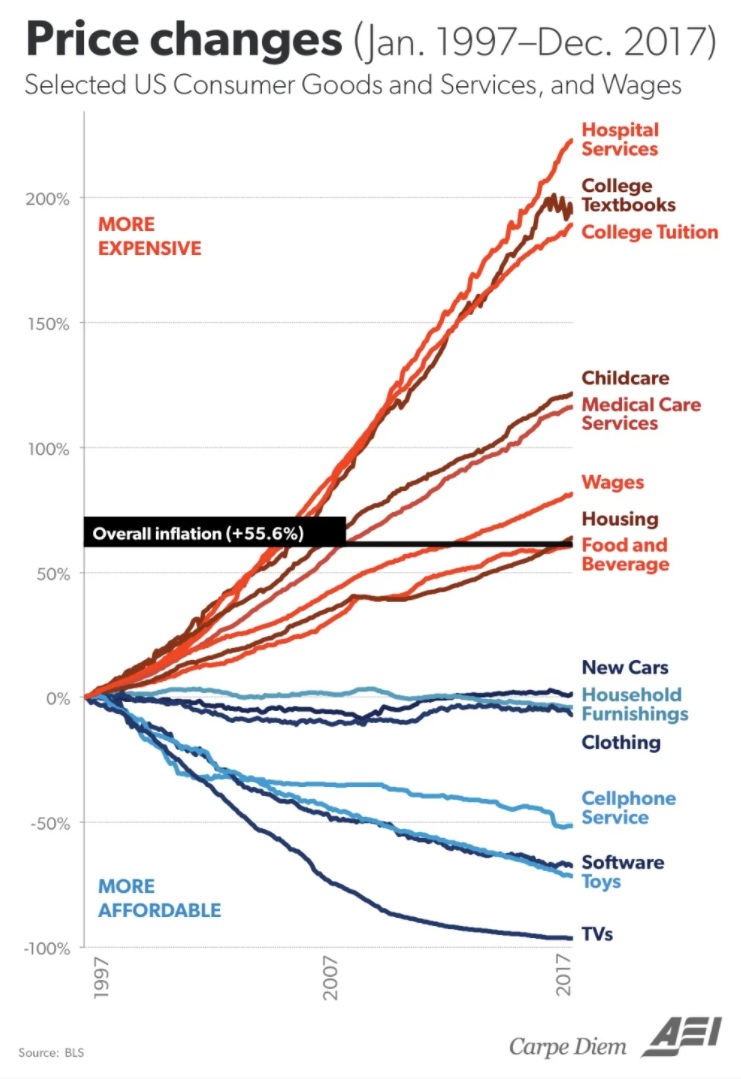

As has been pointed out countless times by various analysts (and confirmed by BLS data), there's a significant variation in inflation rates among the various categories of expenses over time:

Some of these categories inevitably change in importance as we age, with childcare, medical care, and college tuition being among the most notable.

As investors, then, our investing approach should also change depending on whether we're saving (and investing) for retirement, for our kids' college tuition, or for a down payment on a house. The higher the expected inflation rate on the goods we're expecting to purchase, the higher our required investment return on our savings needs to be, all else equal.

Income level

Just as our age will impact the "mix" of goods that we consume, so too will our income level, though the manner in which that impact plays out remains the subject of significant disagreement. Many economists feel that inflation tends to impact the poor the hardest (one study in the UK found that realized inflation was 50% higher for the poor), but others question those conclusions. Among the factors that could be in play is the role of technology products, which are naturally deflating goods but tend to represent a much smaller expenditure (in percent terms) for the poor than for the rich.

Regardless of the overall level of inflation between rich and poor, it is clear that the inflation rate for the poor is significantly more volatile. Because certain costs, like food and energy, are effectively fixed costs—you consume the same basic amount of them whether you're rich or poor—these items tend to consume a much larger portion of the poor person's budget than the rich person's budget. Indeed, according to some estimates, the poorest 20% of Americans spend nearly 60% of their after-tax income on food and energy, whereas the richest 20% spend barely 10%. And since food and energy prices tend to be among the most volatile components of the CPI (so volatile that the Fed likes to strip them out of the CPI in order to measure "core" inflation), it stands to reason that such volatility will also flow through to the poorer individuals' personal inflation rates.

The impact of this disparity on an investing strategy may not be terribly extreme—most individuals who have portfolios to begin with are, by definition, at least somewhat higher income—but retirees on fixed incomes may nonetheless feel the pinch if one of their larger categories of spending sees a larger-than-normal rise in price.

Housing status

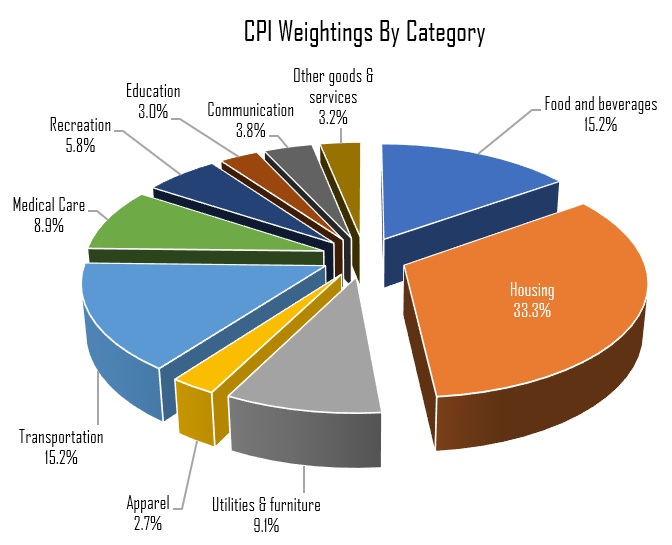

Without getting too deep into the technical details, it's important to recognize that while housing cost is the most heavily-weighted component in the CPI (at more than 30%), it's measured in a way that isn't necessarily reflective of real-world realities.

Source: BLS

Most of the measurement issues derive from discrepancies in costs between those who own and those who rent. Apartment rents don't necessarily track housing prices on a one-for-one basis, and even if they did, not everyone in the country rents their primary residence.

For most homeowners, direct housing cost is essentially a fixed cost, deriving from their mortgage and the price of their home when they purchased it. So while changes in housing prices will have an impact on their overall net worth, they won't typically have much of an impact on their out-of-pocket expenses. But for renters, these costs can and do tend to vary over time, and therefore changes in rents must be monitored and accounted for.

There are a wide variety of market-specific factors that impact whether the majority of individuals will choose to rent or buy, and even more factors that will impact the changes in housing prices and rents. All told, housing costs are an incredibly difficult factor to track over time, and therefore an area of the CPI calculation that has a huge "error" factor attached to it.

Housing, ultimately, is probably the most personal of all the components of our budget, and it therefore doesn't lend itself to a catch-all measurement of price inflation over time. Are we buyers or renters? If we're renters, are we renting a rent-controlled New York City apartment, or a loft in a rapidly-appreciating San Francisco building? And are we hoping to buy in the future, and therefore saving up for a potential down payment?

All of these factors will impact not only the level of our future financial needs, but also how we should (or need to) invest in order to meet those goals. Someone who lives in Iowa and owns his home free and clear is in a decidedly different position from a younger person living in California who hopes to buy a house in the next three years; to pretend that their future expenses will be similar is to miss the point entirely. Does that fact justify a more aggressive investing approach for the young Californian? Quite possibly, yes.

The bottom line

When we're choosing an appropriate investing approach—or even just evaluating our own portfolio performance—the only truly meaningful metric is our achieved (or realized) return versus our required return. What "the market" has done is largely irrelevant to our personal financial situation, unless that market performance has measurably changed our future financial needs. For most investors, it's all too easy to focus on short-term market returns and lose sight of the big picture.

Of course, that point of view might seem sacrilegious to many investors, who have grown up surrounded by a financial media that is seemingly obsessed with chasing market outperformance. But for most of us, the alpha we should be focusing on is not our portfolio return versus the benchmark index return, but our portfolio return versus our own personal inflation rate.

If we're not clearing our own inflation rate, then it doesn't matter if we're beating the market; we're falling behind either way. On the contrary, we may not need to beat (or even meet) the broader market's returns if our inflation rate is low—just treading water with a conservative, low-return approach might be sufficient.

Financial planning and investment planning must always work in conjunction with each other. An investing strategy that does not take expense trends into account is incomplete; to reliably meet your future financial needs, a holistic approach is vital. Do you know what your required return is?