In most market environments, the stock market commands the vast majority of investors’ attention—with heightened risks and returns, the “action” is notable, and the price movements are typically fairly intuitive and easy to follow. The bond market, on the other hand, is generally the ugly duckling of capital markets. For amateurs and professionals alike, bonds can somehow manage to be both boring and confusing, presenting an alien vocabulary all their own. Terms like “duration”, “convexity”, and “yield to maturity” don’t exactly make for riveting cocktail party conversation, but a fundamental understanding of bond market basics can be vital in order to understand portfolio returns, particularly in times of elevated uncertainty.

So far in 2022, with a combination of stubborn supply chain constraints and new geopolitical risks arriving on the scene, interest rate volatility has suddenly surged, causing upheaval in the usually staid fixed income markets. With all eyes on the Federal Reserve and its monetary policy decisions, rising interest rates led to the worst quarterly performance for bonds in 20 years. But what causes bond prices to fall, and what do selloffs in the fixed income space typically mean for future returns? We’ll walk through some bond market basics, in order to help explain what might come next.

Bond pricing basics

On their face, bonds are fairly simple instruments: a borrower (typically a corporation or a government agency) borrows money from investors in the capital markets, promising to do two things. First, they pledge to pay a certain amount of interest (the coupon rate) on fixed dates for a set period of time. Then, they also promise to repay the full amount of the original loan (principal) at the end of that set period (maturity). Both the amounts and the dates are fixed at the time that the bond is issued, which is why bonds are often referred to as “fixed income” instruments. There isn’t much in the way of surprises when it comes to bonds—as long as you hold the bond to maturity and the lender continues to honor its obligations, your bond’s investment return is “locked in” on the day that you purchase it.

But like stocks, most bonds do continue to trade freely in the secondary markets, which means that their prices are subject to fluctuation over time, even if the payments owed (and made) by the lender do not change. The biggest determinant of the bond price is the current market interest rate—the lower the rate goes in the future, the more investors will be willing to pay for that fixed stream of interest payments, and vice versa. If rates climb higher, that fixed income stream might not be as attractive as it once was; a bond investor could do better by buying a newly-issued bond from the same company, with higher periodic payments. So, the “existing” bond will typically decrease in value as rates rise, since its fixed payments are no longer competitive in the new, higher-rate environment.

In certain ways, the bond market can be thought of as somewhat similar to the real estate market. For purchasers of real estate, the lower rates go, the less they will owe each month in interest (for a given loan amount), which typically means they’ll be able to afford to pay more for their home of choice. But when rates increase, the interest burden rises, and the borrower can afford less principal for the same monthly payment. Interest rates and real estate prices therefore have something of an inverse relationship, and so too do bonds. In both cases, the prevailing rate changes the amount that new buyers are willing (or able) to pay for the underlying investment. This dynamic is known in the bond market as “interest rate risk”, and it is a primary determinant of bond returns in the short run.

How bond funds are different from individual bonds

In our previous section, we mentioned that for any given bond, the payments (both of interest and of principal) are fixed at the time of issue, which means that the investment returns are set as long as the bond is held to maturity. But in the case of bond funds, that basic math becomes more complicated. In a bond fund (either a mutual fund or an ETF, typically managed by a large financial institution), there is not just one bond but hundreds or more, each with unique coupon rates and maturity dates. The fund will have an average interest rate (the interest it passes through to investors from the many bonds it owns), but that interest will typically vary from month to month, and the bonds that comprise the fund will constantly be changing as certain bonds mature and new ones are purchased.

Those differences can create both good news and bad news for bond fund investors. No matter what interest rates are doing, there will always be at least some bonds maturing, the proceeds of which will then be immediately reinvested in newer bonds at whatever the new market interest rate is—in times of rising rates, this can be a good thing, but in times of falling rates, it is less helpful. Either way, the investment return on a bond fund is not purely fixed like it is for an individual bond—both the interest payments and the price of the bonds can fluctuate together, creating enhanced volatility when rates are moving quickly. Bond funds can still provide an important diversifying role in a portfolio, but it is important to understand how their performance can differ and fluctuate in various market environments.

The big picture of bond market selloffs

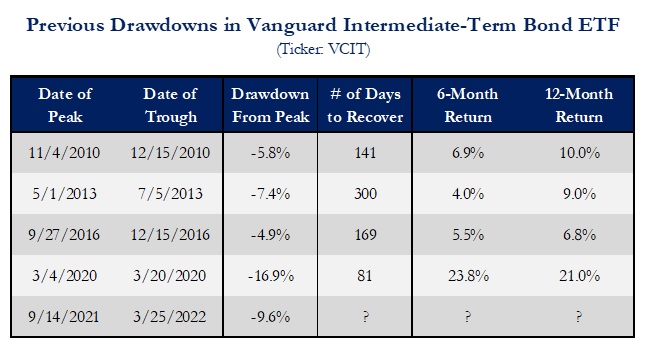

In an environment defined by a very active Federal Reserve, periods of rising rates are increasingly common, even if many of them are short-lived. Therefore, we can look to history to give us some indication of what we can expect going forward. Four times in the last dozen years, the broader bond market has experienced a total-return decline of 5% or more, from peak to trough. In each prior instance, once interest rates stopped climbing, the benchmark bond funds quickly recovered their losses, usually within six months. These relatively rapid recoveries were due in large part to the increased interest payments that the funds boasted as a result of the rate increase.

Over long time horizons, the price volatility caused by changes in interest rates tends to even out, allowing the bond fund investor to enjoy a relatively stable and predictable return. But in periods of rising rates, the decline in price can easily overwhelm any interest payments that are accumulating, raising alarm for investors who aren’t used to seeing fireworks on the “boring” side of the portfolio. But it’s worth noting that in periods when bond rates are falling, bond funds will typically provide returns that are above expectations, in a way that can easily be ignored or missed entirely. It’s too early to know when that period might arrive, but much like with stock investing, a focus on the long term remains vital.