After a year marked by pandemic-related closures, lockdowns, and economic pain, the story so far in 2021 has been one of recovery. With COVID vaccines now widely available, restrictions have been removed throughout the country, and the result has been a much faster economic recovery than just about any expert had predicted coming into the year. Unfortunately, rapid economic growth is often accompanied by rapid price inflation, as demand increases run up against supply constraints. And since both fiscal and monetary policy remain firmly in “easing” territory, concerns about inflation have become rampant over the last couple of months.

According to the official inflation figures, prices increased by 0.64% in the month of May (7.7% annualized), with a year-over-year increase of 5% since last May, far above the Federal Reserve’s long-term target of 2%. Inflation in some areas (building lumber, for example) has been far higher, leading some prominent economists to sound the inflationary alarm bells. Investing legend Warren Buffett and former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers are just two of a growing chorus of voices who have warned of runaway inflation risks unless there are significant and immediate economic policy changes. So, is inflation really here to stay, and are meaningful portfolio changes necessary to combat its effects? We’re skeptical, and we’ll explain why.

Inflation basics

When considering inflation rates, it’s first important to recognize that there’s really no such thing as a “one-size-fits-all” inflation rate. The Bureau of Labor Statistics produces the most commonly cited inflation statistics, all of which consider a weighted average of a variety of different products and services, meant to model the spending patterns of an “average” American consumer. But, of course, there are significant variations in consumption patterns based on a variety of factors, from geographical elements to personal tastes and interests, to even seasonal differences. Not all people purchase the same items in the same amounts, and not all items are increasing (or decreasing) in price at the same rate at the same time. Sometimes those differences can be substantial, and the variation among categories can have a significant influence on the weighted average calculation, as well as the “personal inflation rate” that any individual actually sees in their daily life.

Over the last decade, for example, prices for technology products and services have been flat (or declining), whereas prices for medical care, higher education, and other professional services have increased greatly, by 5% per year or more. Understanding the impact of this variation is always important, but particularly relevant today as we begin to emerge from the pandemic economy.

Indeed, energy prices alone increased by 28.5% over the last year, contributing a significant amount to the headline inflation statistic. The increase in energy prices should not be a surprising development, given where we were just 12 months ago—remember, with travel essentially shut down last spring (airline travel plunged by more than 90% at the peak of the COVID lockdowns), crude oil prices took an unprecedented dive, actually marking a negative price at one point last April as storage concerns outweighed any fundamental value of the commodity. With Americans now rapidly returning to pre-pandemic travel patterns, energy prices are surging. To further complicate matters, a May cyberattack forced the temporary shutdown of a major southern pipeline, constraining supply and causing additional pressure on prices.

This same dynamic is occurring throughout the economy, as battered segments of the economy suddenly lurch back into motion all at once. The sudden restart complicates our usual measurements, since we’re comparing to an unusually low price level from last year (a dynamic known as the “base effect”). Indeed, if we compare today’s price levels to pre-pandemic price levels, we see that cumulative inflation is actually right in line with longer-term trends, with only about 1% of “extra” inflation showing in the current figures. The broader context is always important, and sometimes our traditional statistics do not tell the whole story.

Market-based indicators

For most people, though, the concern isn’t necessarily where prices are today, but where they might be six months or a year from now—current rates of inflation are manageable if they are temporary, but not so much if they persist. The labor market is one major area of current concern, with most small businesses reporting that they have been unable to fill their open positions. Many firms have already been forced to increase wages to attract people back to the workplace, with those cost increases passed through to the consumer via higher prices. If this labor market shift proves to be a long-lasting legacy of the pandemic, then it’s very possible that we will see higher structural inflation for a number of years to come, as the broader economy gradually adjusts to a new labor cost reality.

That said, if we look to the market to see what the “smart money” is currently expecting, most indicators we see are fairly reassuring, at least for now. First, we can simply look at the bond market to see what’s happening with longer-term interest rates. If inflation is expected to increase (or just remain high), then bond yields will generally increase as well, since investors want to make sure that the interest they earn at least keeps up with inflation. However, the opposite has been occurring in recent months. After increasing rapidly earlier this year, the rate on the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond has recently been trending downward, suggesting that inflation fears are easing, not surging.

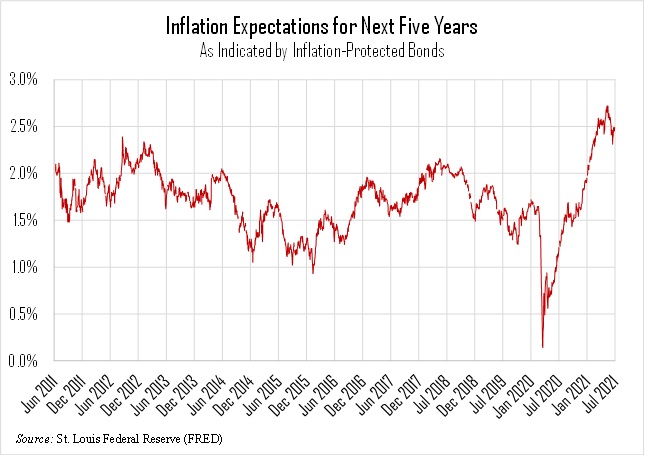

We can also examine rates on inflation-protected bonds (Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities, or “TIPS”), in order to get an indication of how much inflation bond investors are expecting. This measure, known as the “TIPS spread”, is one of our more reliable indicators of inflation expectations. As of the end of June, TIPS prices implied an average inflation rate of about 2.5% over the next five years—above the Fed’s 2% target, but not by much, and again, declining in recent weeks. TIPS may not be a perfect predictor of inflation (nothing is), but if persistent inflation is indeed on the way, the market isn’t seeing it just yet.

The pandemic lockdowns created an incredible number of economic anomalies, and we continue to see those abnormalities as we attempt to emerge back to a more “normal” economy. It will take time for supply chains (and policy measures) to adjust to post-pandemic life, and inflation is a symptom of that adjustment period. We still mostly expect it to ease with time, but persistently high inflation is definitely a risk. Therefore, where appropriate, we are adding some additional inflation protection to portfolios, especially for individuals with high levels of bond holdings.

The information provided in this post is for educational purposes only and is not intended to provide any investment, tax, or legal advice.