For most of the last decade, decisions about how to manage our cash have been fairly simple and low-stakes—with interest rates stuck at rock-bottom levels in the aftermath of the financial crisis, savers became accustomed to their bank accounts paying little or nothing. Low rates also allowed for affordable home equity loans and lines of credit, meaning that for homeowners, additional cash could be obtained relatively cheaply if necessary.

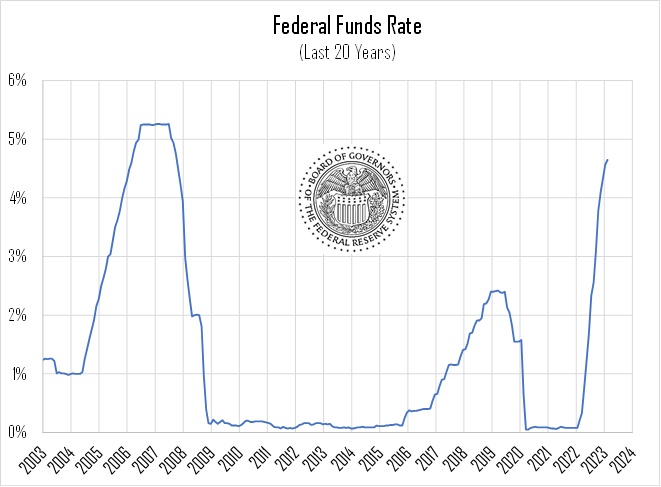

But with the Fed aggressively hiking interest rates to the highest levels in over a decade as its fight against inflation continues, cash management decisions have become much more complicated. Deciding how much cash to keep on hand is no longer a trivial exercise, as “opportunity cost” has abruptly re-entered the conversation. For the most part, this is a very good thing, generating many more options for savers and investors alike. But the new environment can be daunting, and we’ll help you navigate some of the relevant tradeoffs.

Managing your liquidity

The standard recommendation in the financial planning industry is to maintain a fully liquid “emergency fund” at all times, equivalent to 3 to 6 months of living expenses. This basic level of liquidity—typically held in a demand-deposit account like a standard checking or savings account—serves two distinct purposes: first, to cover any major unexpected expenses (home repairs, medical costs, car maintenance, etc), and second, to protect against any income disruptions due to job losses or changes. For individuals or families whose income is particularly volatile or variable, it might make sense to keep a larger-than-normal emergency fund, in order to help smooth the ride—as high as 9 to 12 months could be justified, depending on the circumstances. On the other hand, for individuals with more stable income and expense profiles, a smaller buffer might suffice, perhaps closer to the 3-month end of the spectrum.

Once the “emergency fund” bucket has been filled, any excess cash amounts can be repurposed for other financial needs. Of course, every individual has a unique set of financial circumstances, and a hierarchy of financial needs. Some cash may be needed on an intermediate timeline (savings for home purchases, car purchases, tuition, or otherwise), whereas other money might better be classified as retirement savings, with a much longer investing time horizon. The appropriate level of investment risk (and, related, illiquidity) must then be balanced with the expected time horizon for cash needs.

Traditionally (or at least for the last decade), the recommendation for short-term “emergency fund” money has been to essentially ignore any interest rate that might be earned on these accounts, and to instead prioritize immediate access to funds. Timely access is still crucial, but in the current environment—with higher interest rates meeting ever-improving financial technology—it is now possible to earn a reasonable return without necessarily sacrificing too much liquidity. A number of different companies now offer online high-yield savings accounts with competitive interest rates, often with no minimum balances and high availability to funds, as soon as next-day.

While these accounts’ crediting rates can often lag the overnight Federal Funds Rate, annualized rates between 3.75% and 4.25% have become common, often from well-known and reliable players in the financial industry. For individuals who are willing and able to sacrifice a bit more liquidity, products like CDs or Treasury bills can also be worth considering, and are generally available at attractive rates with terms of less than a year.

Alternatively, your existing bank might offer access to money-market accounts, which can provide more attractive yields while still retaining the convenience and liquidity of a standard bank account. These accounts typically place restrictions on transactions (no more than 6 withdrawals per month, for example), but they do retain full FDIC protection, up to the applicable limits. Note that this FDIC treatment applies only to money market accounts, and not to money market funds, which are a different type of investment vehicle with different levels of protection. Either way, considering the various options available at your existing bank is worth taking time to investigate, in order to strike the right balance between liquidity and earning power.

Rethinking debt management

As was briefly mentioned in our introduction to this piece, when rates were lower, gaining access to cash was a simpler task. Home equity loans (or other similar securities-backed vehicles) were generally easy to secure, and typically offered at relatively attractive rates. That is no longer the case, with the average home equity loan interest rate now exceeding 8%. Furthermore, most mortgages that were secured in the last few years are now inexpensive compared to current interest rates, thereby changing the arithmetic of how we should approach debt management.

At many times in recent years, retiring debt at an aggressive pace was a reasonable strategy, and at least as good as investing the same cash in an interest-bearing investment. If your mortgage was at a 3.5% fixed interest rate, your bank account was paying zero, and even less-liquid CDs and similar products were yielding 2% or less, then “earning” a guaranteed 3.5% return by overpaying your mortgage was an attractive option, particularly for debt-averse individuals. But today, that math has changed, and you may be better off—at least in the shorter term—directing that excess cash toward a guaranteed-rate account instead, paying only the minimum toward your mortgage or other low-rate loan, and reconsidering at some point in the future, if (or when) bank account rates slide back to lower levels. In the current environment, a tactical approach is warranted, and can be richly rewarded.

Other considerations

Given recent developments in the banking sector, it seems necessary to discuss bank risk, if only briefly. For most individuals, bank account balances are low enough that FDIC limits ($250,000 per depositor, per bank) are not breached, and safety of funds is not a primary concern. However, if a bank does fall onto hard times, even if FDIC insurance does eventually make depositors whole, funds could be temporarily frozen while the bank’s issues are sorted out. So, even at smaller total balances, it may still be a good idea to spread funds across multiple financial institutions.

If you have any questions about how you should be managing your cash, please contact us. After all, investing isn’t only done in retirement accounts, it is also done in bank accounts and in our day-to-day lives.